Alright, today let’s talk about the last ACLS algorithm, cardiac arrest. This protocol can be broken down into two parts. The first thing you need to do in cardiac arrest is obviously perform Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and deliver ventilations via bag valve mask (BVM). Next is to attach the cardiac defibrillation pads and determine what rhythm they are in. If the patient is pulseless, this will be one of these four rhythms:

- Ventricular Fibrillation (VF) – This is a bizarre zigzag with no regularity what so ever

- Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia (pVT) – Note that the name of this rhythm includes “pulseless”, that is because this rhythm can also have a pulse. Only pVT is included in this algorithm. This rhythm can be further dissected into Monomorphic or Polymorphic VT, but we will talk about that in a little bit

- Asystole – Cardiac flat line, no electrical conduction

- Pulseless Electrical Activity (PEA) – Cardiac conduction is working great, but there is no physical function of the heart. I like to compare this to a house. The house has electricity, but the water is out, so you aren’t going to have any hot water. This rhythm can be ANY cardiac rhythm without a pulse

So, you need to determine which of these four rhythms the patient is in currently. Now, patients can go back and forth between these rhythms, so every time you do a pulse check (every 2 minutes), then you need to recheck what rhythm they’re in. Now let’s break this down into the two different treatments:

Ventricular Fibrillation (VF) & Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia (pVT)

The first treatment besides CPR and ventilations is cardiac defibrillation. You place the cardiac pads on the patient and defibrillate according to your monitor’s settings (biphasic=120-200j, monophasic=360j). Following this defibrillation you immediately resume compressions for two minutes and obtain IV access if you haven’t already. The first medication you will administer will be 1mg of 1:10,00 Epinephrine. After the 2 minutes, you are going to pause compressions and check for a pulse. If the patient is still pulseless and in pVT/VF, then you are going to defibrillate again, and go right back into compressions. 3-5 minutes after the Epinephrine administration, you are going to give 300mg of Amiodarone or 1-1.5mg/kg of Lidocaine. You are going to repeat pulse checks & defibrillations every two minutes. After another 3-5 minutes from the Amiodarone administration, you are going to give another 1mg of Epinephrine. The next medication after another 3-5 minutes, you will give 150mg of Amiodarone or 0.5-0.75mg/kg of Lidocaine. After the second dose of Amiodarone, you will just give 1mg of Epinephrine every 3-5 minutes for the duration of the arrest. So long story short, its:

- 1mg Epinephrine

- 300mg Amiodarone or 1-1.5mg Lidocaine

- 1mg Epinephrine

- 150mg Amiodarone or 0.5-0.75 mg Lidocaine

- 1mg Epinephrine

- *repeat 1mg Epinephrine until the cease of resuscitation

Asystole/PEA

The steps for asystole/PEA are the same as pVT/VF, with the exception of the defibrillations and Amiodarone administration. For these rhythms, initial interventions are going to consist of 1mg of Epinephrine every 3-5 minutes. We don’t defibrillate these patient’s because defibrillation is only reorganizing cardiac conduction. With asystole, there isn’t cardiac conduction to reorganize. PEA is a great cardiac conduction; however, the “pump” isn’t working, so defibrillating the patient isn’t going to fix the problem. The most common causes of Asystole/PEA are hypoxia and hypovolemia.

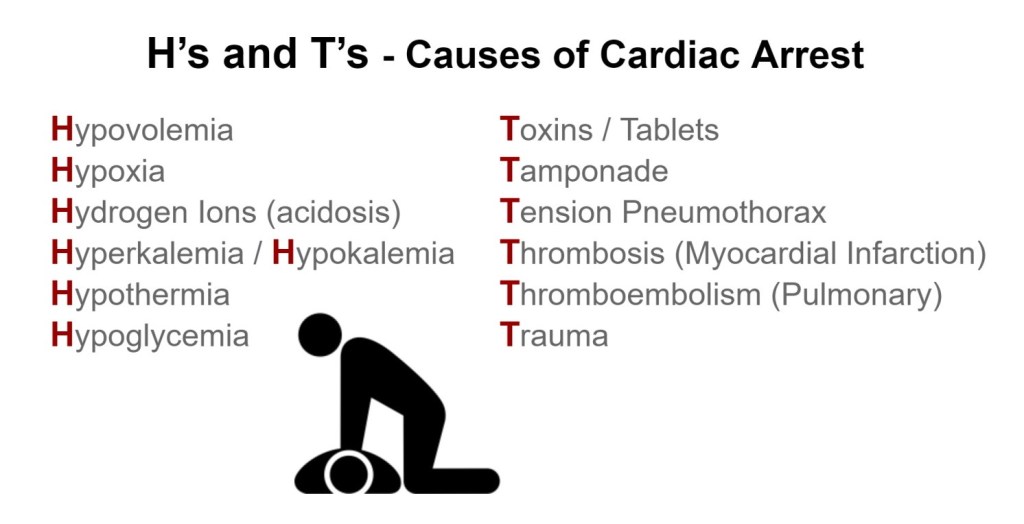

Causes???? Let’s talk about causes…

These two algorithms have something in common with the other algorithms we have discussed and that is we need to address the underlying cause. The treatments for this algorithm are going to be referred to as the “H’s & T’s”:

- Hypovolemia – How do you know if the patient is hypotensive in a cardiac arrest? That’s right, you can’t. This is one of those things you just treat until proven otherwise. Administer a fluid bolus. If the patient has a history of Congestive Heart Failure (CHF), we can treat the fluid overload later. Hypovolemia is one of the most common causes of cardiac arrest.

- Hypoxia – Hypoxia is one of the most common causes of cardiac arrest as well; this could be caused by many causes (respiratory failure following an MI, CVA, COPD, sepsis, and even an overdose). This treatment is obviously treated while you’re ventilating the patient; however, it still needs to be addressed and make sure the BVM is attached to oxygen.

- Hydrogen Ions (Acidosis) – This treatment greatly depends on your capabilities and location. In a hospital or clinic setting, you can check lab values to determine if the patient is metabolically acidic. In the pre-hospital setting, this may not be an option. In this case, we must go off of the Capnography reading. If the patient has a Capnography <35mmHg, then 1mEq/ml (1 amp) of Sodium Bicarbonate may be indicated.

- Hypo/Hyperkalemia – This is another one that’s difficult for pre-hospital, but standard practice for in-hospital or clinic. Obviously if you can take lab values, you’ll know if their potassium level, but what if you can’t? Before the patient coded, if hyperacute “T” waves were present, then this could be an indicator that the patient was possibly hyperkalemic. In this case, you could consider 1g of Calcium Gluconate or 1mEq/ml of Sodium Bicarbonate.

- Hypothermia – This is both one of the easiest and hardest conditions to treat, both pre-hospital and in-hospital. Active warming the patient is paramount to combat this finding. For EMS, that’s warming the back of the truck and blankets if you have them. You can also place warming pads in the groin and under the arms, but be cautious of causing burns to the skin. Hospitals have more advanced equipment such as a Bair Hugger Temperature Management device that can be placed on the patient. Hypothermic patients commonly present as PEA/Asystole.

- Tension Pneumothorax – This is caused when the plural cavity has been punctured and allowing air to fill the space, or blood in the case of a hemothorax. This will in turn cause pressure on the lung causing it to “collapse.” This condition can be noted by distant lung sounds (or muffled in the event of a hemothorax) and unilateral chest rise, as well as tracheal tug and/or jugular vein distention (JVD) in late cases. Treatment for this includes needle decompression or chest tube placement. The patient could possibly have a bilateral pneumothorax, which obviously will be harder to determine due to the signs and symptoms being bilateral.

- Tamponade, Cardiac – Tamponade is similar to hemothorax, in that it is due to blood build up to the cavity around an organ; however, this time the organ is the heart. Pericardiocentesis is the treatment for this condition, which is reserved for physicians only. This can be noted by muffled heart tones or Electrical Alternans, or “swinging” of the cardiac amplitude on a 12-lead ECG.

- Toxins – This one is a MASSIVE umbrella. “Toxins” refer to ANYTHING in the body that should not be there. That could be an intentional or unintentional overdose. If the patient is suspected of a beta blocker overdose, then 1g of Calcium Gluconate or 3mg of Glucagon should be administered. If the patient took too much of their insulin, then 25g of D50 (or 250ml D10W) may be necessary. Lastly, if the patient overdosed on an opiate, then this could have caused respiratory arrest. In this case, the treatment is O2 via BVM like you’re already doing. In the 2015 AHA guidelines, 0.4-2mg of Narcan was administered in the event of an opiate overdose induced cardiac arrest. This has since been removed from the AHA guidelines. The reason for this is because Narcan will only un-block the opiate receptors that cause respiratory failure. You are bagging this patient with a BVM; therefore, this medication is not needed. Now, some services have left this treatment in place, so know your service’s policies and procedures.

- Thrombosis (Pulmonary & Coronary) – Finally we have the two thrombosis-es. Neither of these can be treated during an arrest; however, they need to be considered in the event or Return of Spontaneous Circulation (ROSC). If ROSC is achieved, a 12-lead ECG needs to be immediately obtained to rule out a possible STEMI. A pulmonary embolism also needs to be considered, unfortunately these patients have a history of poor outcomes

There is no allotted time frame for these “H’s” & “T’s”; however, they need to be addressed as quickly as possible to increase the patient’s chances of survival.

If ROSC is achieved, a pulse, blood pressure, and 12-lead ECG need to be taken as soon as possible. The patient should be treated with targeted temperature management 32-36*C for the first 24 hours and closely monitor them for changes.