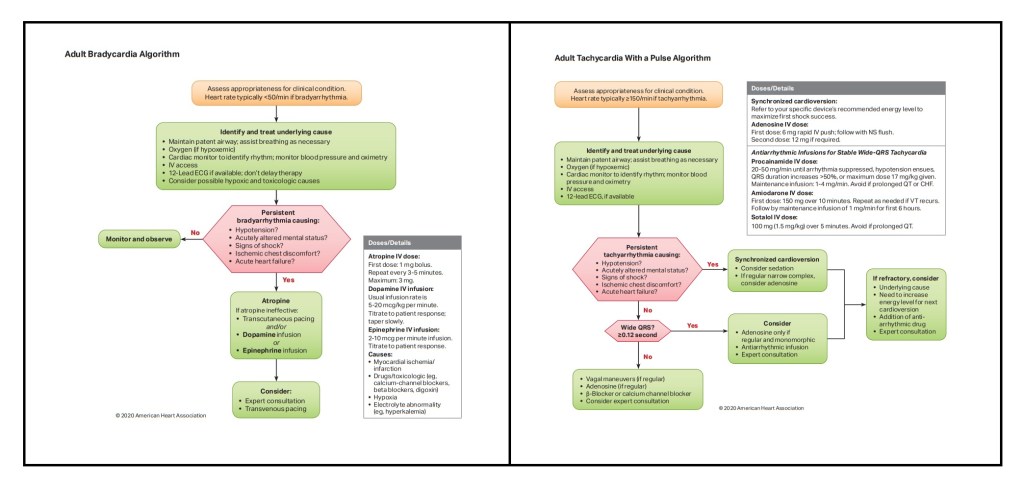

In today’s blog we will be continuing our review of the American Heart Association’s Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) Course. We will discussing the Bradycardia and Tachycardia Algorithms.

For the following two treatment algorithms, there are three important things to note:

- The primary concern with these patients is to treat the underlying cause. If you don’t treat that, you can treat symptoms all day, but it won’t fix the issue.

- Initial treatment is identification of if they are stable or not. I like to refer to these patients as being either unstable or “stable-ish.” At the end of the day, a patient isn’t stable with a resting heart rate of 200. What makes them “stable-ish” vs. unstable depends on their presentation, mainly are they compensating. Blood pressure is going to be your easiest determining factor of if they are unstable.

- You want to treat these patients with the least amount of intervention as possible. If you can treat them by coaching them through some basic techniques, over medication, then it’s a good day. ALWAYS BLS BEFORE ALS!!!

Bradycardia

Defined as any heart rhythm <50bpm, this may include, but is not limited to: sinus Bradycardia, Atrial Fibrillation, Junctional Escape, or any of the heart blocks. Like we said before, BLS before ALS, so attempt the least invasive thing first. If your patient is symptomatic and unstable, then you need to go immediately to transcutaneous pacing, which we will discuss in just a minute. The first “treatment” for this patient is to attempt to excite them. This may sound pointless, but exciting them can make the heart increase to an adequate rate while you assemble your equipment. After establishing an IV, you can begin with your medication administration for these patients. While it is not in the AHA guidelines, a fluid challenge can be very beneficial in a bradycardic patient. If that doesn’t work, the next thing you want to do is give 1mg of Atropine. You can give this medication two more times, to a max of 3mg. If the Bradycardia is originating from the atrium, the Atropine should increase the heart rate alone; however, if they are having a 2nd Degree Type II or 3rd Degree Heart Block, then this medication will not be effective.

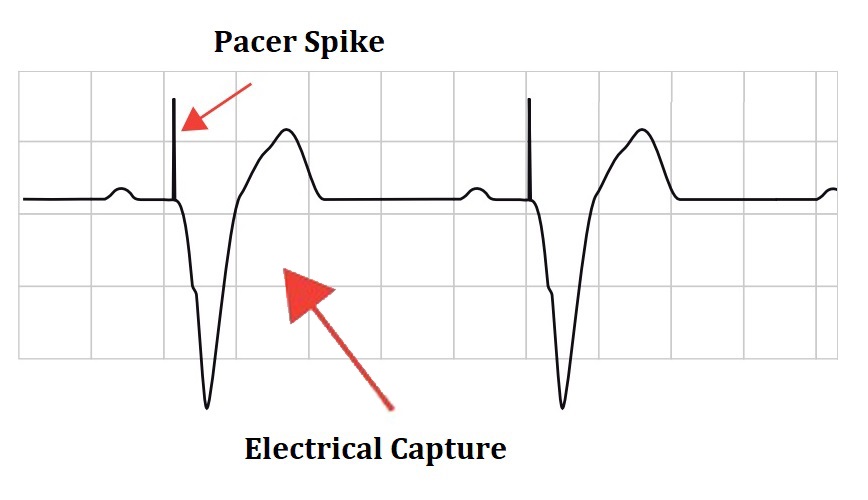

If the patient is still bradycardic, then you need to move on to transcutaneous pacing. You do this by placing defibrillation pads on the patient. If the patient is “stable-ish” you should consider a sedation drip for comfort. Pacing isn’t going to be the worst pain ever, but it won’t be enjoyable either. The patient will experience the equivalent of when someone rubs their feet on carpet and then shocks you when they come into contact with your skin. The only difference is, they will get this little jolt at the rate you set your monitor to. You will turn your monitor into “pacing” mode and set your rate (typically 60-70bpm). At this point you will slowly increase the voltage, mAh in this case, until you get what’s called “Electrical Capture.” Capture is when you have a QRS segment after every pacer spike on the monitor. At this point, AHA suggests decreasing the mAh until you lose capture and then increase by 10%. The reason for doing this is to deliver the least amount of electricity as possible. After you have achieved the required amount of energy to get capture, you need to assess your patient (i.e. vital signs).

If your patient is hypotensive, then you can increase the rate on the monitor to alleviate some of the issues. If that doesn’t work, you can consider an epinephrine or dopamine IV drip. Like I said before, you need to treat the underlying cause. Until that cause is addressed, the problem will still persist. If the patient does not improve from these treatments, Transvenous Pacing may be needed, which is similar but the pacing is done from inside the patient’s heart during a surgery. Ultimately, these types patients will most likely require a pacemaker placement.

Alternatively you can consider a medication drip for these patient’s depending on condition. I’m going to use the “T” word (I apologize to my paramedic instructor haha), but these medications are used to TITRATE the patient’s blood pressure to an appropriate number. You can administer either Dopamine 5-20mcg/kg/min or Epinephrine 2-10mcg/min.

Tachycardia

Defined as any heart rhythm >150bpm, this may include, but is not limited to: Supraventricular Tachycardia (SVT) and Ventricular Tachycardia with a pulse. As with bradycardic, you want to treat these patients initially with the least invasive treatment, if possible (i.e. if they’re stable). The first “treatment” you want to perform is a simple vagal maneuver. The point of this technique is to stimulate the vagus nerve into switching the patient into a parasympathetic response and in turn slow their heart rate naturally. This can be done by instructing the patient to bare down as if they had a bowel movement, blow into clean syringe, or place a cold pack on the face for a couple seconds. In the event that this doesn’t work, you will then need to move into pharmacologic interventions.

You can being with administration of Adenosine. You begin with 6mg of Adenosine IV push. This medication needs to be given fast and as close to the IV site as possible, due to the medication’s short half-life. If 6mg doesn’t work, you can then administer 12mg. This medication causes a temporary block of the AV junction of the heart, which hopefully will cause the patient’s electrical conduction to pause and then go back into a normal sinus rhythm. In the event that this medication doesn’t work, you will need to move to Synchronized Cardioversion.

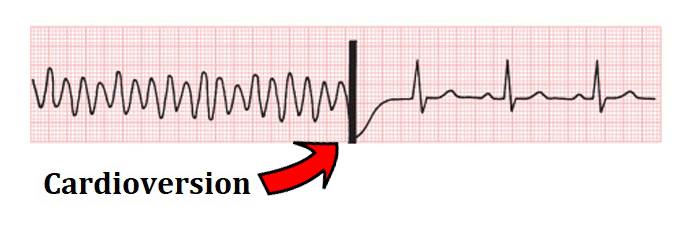

If the patient is “stable-ish”, then you need to consider sedation. This intervention can cause significant pain to the patient, so sedation/pain management would be preferred if it is possible. Common practice is to give the patient a versed IVP until the eyes roll back and then initiate synchronized cardioversion.

To perform this intervention, you place the cardiac pads on the patient. Depending on your monitor, place it into either synchronized cardioversion mode, or into defibrillation mode and then select cardioversion. The amount of electricity depends on your cardiac monitor’s settings. This voltage is written in joules, just like defibrillation. The reason it’s called “synchronized” is because the monitor needs to identify the “R” wave, shown by a triangle or circle over every QRS complex. This needs to be done because the cardioversion needs to occur during the patient’s refractory period.

Following electrical discharge, hopefully the patient converts into a normal sinus rhythm. If they go back into a tachycardic rhythm >150bpm, then another cardioverison with more joules may be necessary.

Alternately, if the patient is in a stable wide-complex tachycardia there are a few medications you can consider:

- Procainamide: 20-50mg/min until the rhythm converts becomes hypotensive, extends QRS duration, or you reach the max dose of 17mg/kg. If the patient converts, then place them on a maintenance drip of 1-4mg/min

- Amiodarone: 150mg over 10 minutes; repeat as needed. If the patient converts, then place them on a maintenance drip of 1mg/min for the first 6 hours

- Sotalol: 100mg (1.5mg/kg) over 5 minutes